Originally Written for English Film Studies in 2002

Introduction to English Film Studies:

In the Autumn of 2002, I analyzed several movies with their respective literary source material.

- Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979) with Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness (1899)

- Todd Field’s In the Bedroom (2001) with Andre Dubus’ short story Killings (1979)

- Tod Browning’s Dracula (1931) with Bram Stoker’s epistolary novel Dracula (1897).

I wrote dozens of research papers in college. But this was one of my favorite assignments. We were allowed to choose which Dracula adaptation that we wanted to research for the final writing assignment.

For many years, I thought this article was lost forever. Recently, I recovered the document on a long-forgotten hard drive.

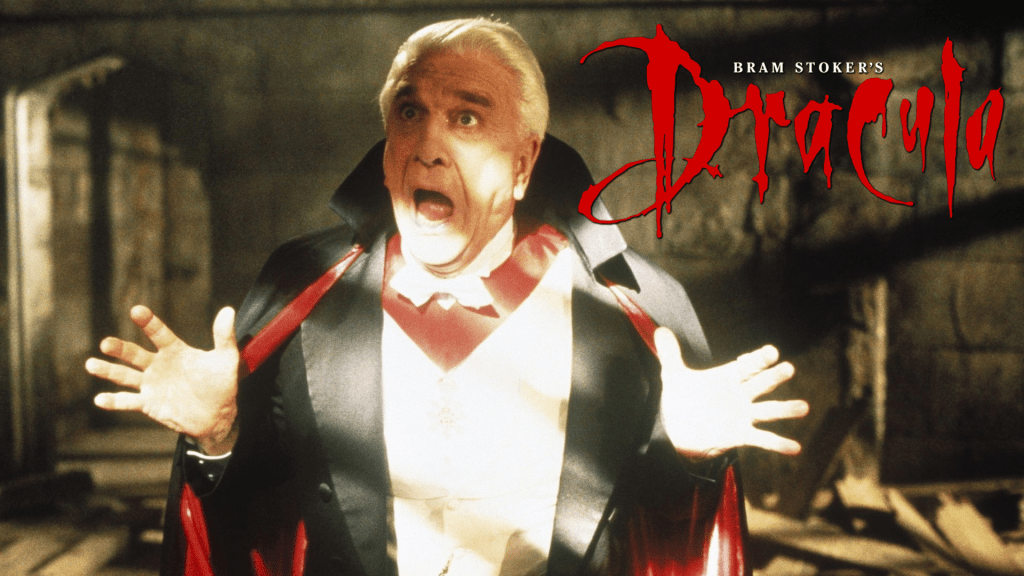

Dracula: Dead and Loving It

“The children of the night. What a mess they make.” – Count Dracula

1995, USA.

Director: Mel Brooks

Screenplay: Mel Brooks, Rudy DeLuca, and Steve Haberman. Based on a story by Rudy DeLuca and Steve Haberman. Based on characters and situations created by Bram Stoker.

Cinematography: Michael D. O’Shea

Editing: Adam Weiss

Cast:

Count Dracula ……… Leslie Nielsen

R.M. Renfield ……….. Peter MacNicol

Jonathan Harker …… Steven Weber

Mina Murray ……….. Amy Yasbeck

Van Helsing ………….. Mel Brooks

Lucy Westenra ……… Lysette Anthony

Jack Seward ………….. Harvey Korman

Plot Summary: Renfield, a solicitor from London, travels to Transylvania and meets Count Dracula. Together, they conclude a business deal on an estate in England. Though, despite many warnings from the townspeople about the supernatural occurrences at Dracula’s castle, Renfield meets the Count. Soon, Renfield is under Dracula’s spell and accompanies the Count to London. While Renfield is incarcerated at a sanitarium, Dracula begins to integrate himself into London’s social class and seduces Dr. Seward’s young ward, Lucy Westenra. When Lucy becomes heavily fatigued, Seward calls in Dr. Abraham Van Helsing, a specialist in rare diseases, as well as “theology, philosophy, and gynecology.” Nevertheless, Van Helsing believes that Lucy has fallen prey to a vampire. He enlists the aid of Seward and his future son-in-law, Jonathan Harker, to free Lucy from eternal damnation. Before long, Dracula sets his sight on Jonathan’s fiancée, Mina. Setting up an elaborate trap at a ball, Van Helsing reveals that Dracula is the vampire. Also, Renfield is exposed as the Count’s accomplice. Dracula kidnaps Mina and plans to make her his bride. Van Helsing compels Seward to release Renfield, who unwittingly leads Van Helsing to the Count’s secret lair. In an epic struggle of good versus evil, Dracula is defeated.

Connections to the Original Novel: Mel Brooks respects the tradition of keeping the characters and historical settings of the novel. Renfield is a patient at Dr. Seward’s sanitarium who is driven insane by Dracula’s supernatural powers. Count Dracula is a vampire from Transylvania who purchases an estate next to Seward’s sanitarium. He seduces Lucy Westenra and Mina Murray. Lucy is a young and beautiful woman who falls prey to Dracula’s spell and becomes a vampire herself. Van Helsing is a doctor who believes in vampires and convinces the other characters of the Count’s true identity. Jonathan Harker is engaged to Mina and must join the fight against Dracula to save the woman he loves.

Thematic Analysis: Bram Stoker used a distinctive narrative style in his novel which utilized several narrators. For example, the use of different narrators offered credibility. There was a sense that these people belonged to a community that needed protecting from Dracula’s evil. Of course, Brooks used an unbiased and cinematic third person format. The film begins with Renfield’s point of view, but quickly changes to Count Dracula and Van Helsing’s viewpoint. Although Brooks draws heavily upon satirizing Stoker’s novel, there are many differences about the themes explored in the film. As a result, the alteration of the source material changed the characters’ motives and feelings about the community around them.

The theme of science and technology is presented differently in Stoker’s novel and Brooks’ film. In the novel, for instance, Van Helsing heavily relied on his scientific background as a doctor. When he investigated the strange circumstances surrounding Lucy’s illness, he empirically observed the evidence. Eventually, he came to the conclusion that a vampire was involved in the young woman’s condition. This emphasized the vital need to use reason and logic as a means to work your way through a problem. Nevertheless, in Brooks’ film, Van Helsing briefly inspects Lucy’s neck. Quickly, he concludes that a vampire was responsible because modern science couldn’t explain the loss of blood in Lucy’s body. When Seward and Harker scoff at the idea, Van Helsing chastises the men for their ignorant reliance on science. It is clear that Brooks’ placed Van Helsing in charge of the group over Seward and Harker. The different viewpoint on science and technology in the film highlights the need to avoid empiricism. Van Helsing relies on supernatural possibilities. Ultimately, science is subordinate to faith and religion.

Nonetheless, the idea that religion and Christianity are powerful tools is still clear in the film. Although they are not infallible tools to defeat vampires, items like the crucifix and garlic can hold Dracula at bay. The weapons are the few physical items that are more reliable than science. It is the only way to temporary save Lucy from Dracula’s powers until redemption can found.

Nevertheless, the theme of redemption is handled very differently by Brooks. Stoker offered a sense of redemption for Dracula, while Brooks offered eternal destruction for Dracula. In the novel, for example, there was a “look of peace” on the Count’s face when Harker killed him. Conversely, in Brooks’ film, Dracula is not saved from his curse. The only hint of a possible redemption comes in the form of a “daymare.” After feeding upon Lucy’s blood, Dracula dreams that he has been cured. He can walk about in the daylight, if only momentarily. Yet, since this event is revealed as a dream, it is unclear whether Dracula would have found redemption. The vampire is obviously appalled by the notion of being a human and associating with the community. Hence, Brooks believes that redemption is something that evil doers do not want to achieve anyway.

Yet, this does not mean Brooks suggests that everyone is doomed to eternal damnation. The film does keep a sense of misguided and unintentional redemption. Since American audiences love individualism, Brooks used an anti-hero in the unlikely form of Renfield to defeat Count Dracula. In the novel, Stoker highlighted the importance of community. It was a group effort that led to the defeat of Dracula and his minions. Yet, in the film, because of Renfield’s obsession in pleasing Dracula, he searches for an escape route. He accidentally exposes the vampire to the sunlight and kills his master.

Ultimately, according to Brooks, redemption from madness is unexpected and not something a person can knowingly set out to achieve.

In the novel, madness was personified in Renfield’s character, while altruism was embodied by Harker. While Renfield still embodies the idea of madness in the film, Brooks does not include such personifications for Mina’s fiancé. Harker symbolizes guilelessness and skepticism. Although Harker knows that Lucy is dead, he is still unwilling to believe it. He almost falls for Lucy’s sexual advances toward him. Van Helsing’s knowledge of vampire lore saves the young man from Lucy. Van Helsing suggests that she must be evil because of her open sexuality and readiness to commit fornication.

The use of sexuality is one of the most important elements in any adaption of Stoker’s novel. Both the film and novel suggest that if a woman becomes voluptuous and sexually appealing, she is truly evil. She must be destroyed for her own good, and for the good of the community. Yet, Brooks slightly changes the use of sexuality in his film. Much like Tod Browning’s 1931 adaption, Brooks made Renfield effeminate. Renfield can’t escape from Dracula because he has unmanly qualities about him that prevent him from resisting the Count’s powers. In fact, Dracula does not even finish his mesmerizing speech before Renfield is under the Count’s control. Yet, when Renfield is around the voluptuous vampire women he does show an interest in them. Also, he becomes sexually aroused by Lucy when he is trying to rid her bedroom of the garlic. Thus, Lucy is already an alluring woman before her transformation as a vampire. For example, Lucy undresses outside on the terrace for the Count’s advantage although she is not a vampire yet. It is only then that Dracula exploits her sensuality and begins seducing her. Brooks suggests that already being alluring is what leads a woman to being “corrupted by the evil of a vampire.” All of this information is revealed quickly and without hesitation.

The withholding of vital details about Dracula’s true identity created tension and suspense in Stoker’s novel. In fact, Dracula disappeared in the middle part of the novel. Rather, the focus was on Van Helsing and the committee’s effort to unravel the case of the mysterious deaths. Although Dracula’s mysterious powers are limited, Brooks does not hide the fact that the Count possesses mind control abilities. In fact, Brooks makes it clear from the beginning that Count Dracula is a vampire. For example, Dracula transforms into a bat and leaves his estate to seduce Lucy. Later, Van Helsing arranges an elaborate trap to expose that Dracula has no reflection in a mirror. The startling revelation is to set up the final confrontation between good and evil. It is not to inform the audience that Dracula is the vampire. Thus, the suspense surrounding Dracula’s identity is not included in Brooks’ film.

Overall, Brooks seemed to be ridiculing Stoker’s novel and other well-known Hollywood adaptations. But he succeeded in crafting together a delightful comedy about the characters and situations created nearly a century ago.